I've already talked about Neon Genesis Evangelion a fair amount, perhaps too much. Some part of me hopes that in writing these I can get that impulse out of my system. It's not likely, though. Yes, Evangelion is my all-time favorite series, but it's also the series which sets a standard for all others in my mind. With some series, the comparison can be fairly direct: in the case of Attack on Titan, another disaster scenario which explores psychological trauma, I felt like Evangelion served as a useful foil. The same goes for the noir/mecha anime The Big O, particularly in its heavily Eva-influenced second season. In other cases, the comparison is far less direct. For instance, the heavily acclaimed series Breaking Bad's fifth (or fifth and sixth) season has lost its luster for me because I no longer get why I should be watching Walter. Did the show only set out to create a smart, capable character who gets under your skin with a particularly infuriating kind of evil? Well, Evangelion already did that using far less fanfare and screentime with Gendo Ikari, who's also smarter, more capable, and more evil than Walter White could ever be. Further, unlike Breaking Bad, Evangelion takes place in a neutral world; it doesn't favor Shinji one bit. Sure, he's more or less the best Eva pilot, but there's a reason given for it. The show never breaks plausibility and logic to favor the protagonist's needs or wants.

Because I want to spend a little more time with Evangelion (I plan to make this a two-part post, followed by a review of the film), I'd also like to make some boiler-plate remarks on the blog so far. First of all, thank you everyone who read, gave feedback, and passed the blog along. It means a great deal. In summary, the feedback I received was largely critiquing an issue with regard to my perspective on anime as a whole, and another issue about my toothless review of Attack on Titan. I'd like to go ahead and address this briefly, because these are excellent points.

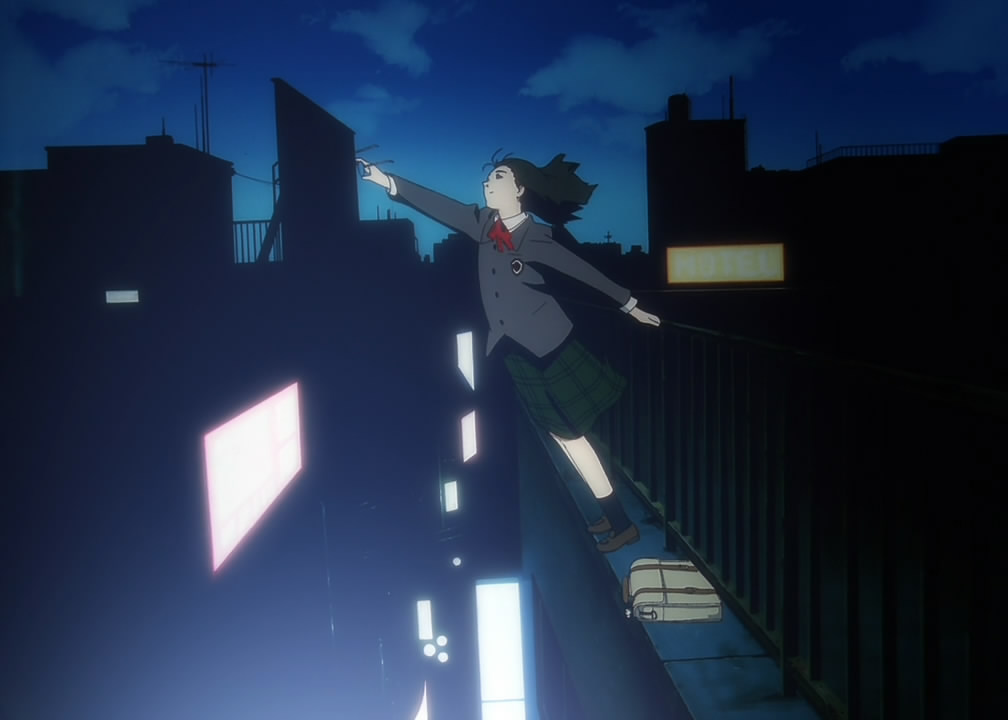

Skip ahead to the next still for the part that's actually about Evangelion.

The first issue presented was that in this blog, I am essentially setting up a "Japanese anime>other animation>live action" model. I will admit, my favorite series are anime (Evangelion, Fullmetal Alchemist, Serial Experiments Lain), but right behind them are Twin Peaks, The X-Files, and Mad Men. I think the short run-time of most anime series works to their advantage, and they can tell detailed, complete stories in a satisfying manner. They have the narrative conciseness of films and the expansiveness of television, and combined with the unique storytelling benefits of animation, they tend to make for better series, in my opinion. Indeed, I find long-running anime series such as Dragon Ball, Bleach and Inuyasha insufferable. Most of my favorite films, however, are live action, by film greats such as Francis Ford Coppola and Stanley Kubrick. In other words, animation is not a prerequisite for greatness by any means.

The other issue was my use of a very contentious word: perfect. Attack on Titan, I am told, is not perfect. I also neglected to point out the thin characterization and erratic pacing plaguing the entire first season. To be honest, though, the pacing didn't particularly bother me at any point. I think it sped up and slowed down for dramatic effect, exactly as it needed to. As for the characters, there are quite a lot of them in Attack on Titan; some of them are conventional characters who are given backstory and detail (Eren, Mikasa), but most of them are representative of a theme. Authority, fear, self-interest, and misanthropy are all themes which Attack on Titan conveys, and some characters are an embodiment of those and other themes (shouldn't be hard to figure out who's who among the four I listed).

But in a larger sense, I view seasons of a show as a totality, a sort of meta-film in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Thus, a great season can still have bad episodes. Indeed, in two of my favorite seasons of television I've watched recently, (Mad Men Season 3 and Breaking Bad Season 4) there were several weak episodes in which I began to lose patience with the respective shows, but as each drew to a close, they revealed a tightly written and logical work expanding over 13 episodes. It didn't matter that Mad Men Season 2 had a more solid and consistent 13 individual episodes; at the end I wasn't transported by their totality in the way I was by the show's far more uneven successive season. Thus, I believe that the totality of Attack on Titan Season 1 did everything it set out to do; it is perfect for what it is. I don't think it will ever surpass Evangelion because the project of Attack on Titan is (amazing as it is to think) less grandiose and less ambitious, and thus I don't think it'll ever reach Eva's olympian heights. But it's still everything I could have wanted from it, and that's good enough for me.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is not a flawless show, either. It is quite unlike Attack on Titan in that its flaws are not buried in the woodwork, only noticeable after the fact. Rather, the flaws of Evangelion scream in your face. From the very first moments of the show, we see that it is tacky and dated, as the synthesized horns blare out a lazily written and tonally inappropriate theme song (don't even get me started on the cover of "Fly Me To the Moon" or its bizarre remixes which function as the end credits song). The show itself has tonal shifts which are utterly jarring and unexplained, often signified by the even more grating flute tune which scores the "lighthearted" scenes, which mostly portray Misato's alcoholism and often feature Shinji being abused in some capacity. If these scenes are intended to be comic relief, the relief (and indeed, the comedy) is lost on me. The show also fails to make Ritsuko a believable character; rather than psychologically exploring her personal life, we are simply told facts about it which make little sense given how little context we have. And although some of them are excellent, episodes 8-15 can feel irrelevant, formulaic, and out of touch with the rest of the show. The most egregious example of this is Episode 9, "Moment and Heart Together". Although Anno and Satsukawa's writing is far below par here (the trick to beat this Monster of the Week is through the power of synchronized dance!), Seiji Mizushima's direction is also jarring and out-of-place, an amazing fact considering his stellar work on another of my favorite series, 2003's Fullmetal Alchemist.

Whew. Okay, I think that's my complete gripe list. I could go into further detail about how I find other episodes like "Magma Diver" lame by comparison, like well-executed episodes of a far less interesting show, but given how much navel-gazing the show ultimately amounts to, sometimes it's good to step into the real world. Although these episodes themselves lack the features which make Evangelion truly unique and great, I appreciate the fact that we are given a complete view of these characters' lives. For most of the show, Shinji is depressed, Asuka is lonely and frustrated with everything, and Misato feels personally vacuous and clings to her status as a sex object to feel a sense of worth. But those are the characters' unique conditions, they are not their entire personalities. They have real moments of triumph, friendship and (perhaps) love. Evangelion is a show where the human characters truly feel human, and the alien characters truly feel alien (with one key exception). The Angels are completely mysterious in their intent. Are their names on the nose? Is their purpose simply to wipe out humanity because humanity's nature is evil? I doubt it. The Angels are inscrutable because it's likely that alien life would have no commonality of language, culture, or behavior to humans. We can't even tell if they truly have consciousness. This is a testament to the way Hideaki Anno's writing works: even though he presents a fantastical situation, the details make it feel true to life.

The first episode of Evangelion is a triumph in its own right, perfectly setting up Shinji's character, and his relationships with Misato, his father, and Eva 01. Shinji's mantra ("I musn't run away!") is somewhat childish, it grates on the mind in a kind of indescribable way. It's also taken directly from Anno's life:

They say, "To live is to change." I started this production with the wish that once the production complete, the world, and the heroes would change. That was my "true" desire. I tried to include everything of myself in Neon Genesis Evangelion—myself, a broken man who could do nothing for four years. A man who ran away for four years, one who was simply not dead. Then one thought. "You can't run away," came to me, and I restarted this production. It is a production where my only thought was to burn my feelings into film. -Hideaki Anno, July 1995.

Shinji is not an audience stand-in, although he may appear to be, as he is introduced to Tokyo-3 and NERV along with us. The audience may see some of ourselves in him (I myself see too much for my comfort), but he is not the sympathetic protagonist featured in most television shows. He's a character whom we pity. He's not "the one" because he chose to be. Indeed, he repeatedly tries to resist his role as humanity's protector. Partially because that's a lot of responsibility to shove on a 14-year old, partially because he feels like he's being manipulated by his father (which he is, and has every right to be sick and tired of), and mostly just because he's scared. In the first episode, as Rei is brought out on a stretcher to be loaded into Eva 01, we see Shinji's main redeeming quality: empathy. It's a characteristic which turns out to be rare in this world, one which his father probably doesn't know exists, much less possesses. Indeed, one wonders where Shinji got it from. Even Misato (who seems to care for the boy in some capacity) simply encourages him for the sole purpose of not dying.

The details about Rei's injury are not explained until a later episode, and while it is fairly obvious that she is simply incapacitated so that Shinji must step into the role of Eva pilot (i.e. the plot requires it), I've always found it extremely apropos of the series. The narrative might rise and fall on Shinji, but the world surrounding him doesn't. In time, we'll get to know the stories of the First and Second Impact before he was even born, and the mysterious passing of his mother. More importantly, most of the central characters of the story have been at NERV for some time. Rei's injury shows that they have been living lives outside of him; they don't just go into carbon stasis when he's not around. On the one hand this is just a nice detail because it makes the world feel lived-in. On the other, it is representative of Shinji's central feeling about himself and others: he doesn't matter to them, life will go on anyway. Isn't that true, though? If you were to die, not only would 99.99% of humanity not know about it, even the people closest to you would ultimately get on with their lives. Shinji knows that he's an unnecessary person, and yet within the first 20 minutes of the show, we see that he's completely central to humanity; or at least to Eva 01, as it mysteriously swoops in to save him.

Misato is not an Eva pilot, but she's nearly as important to the story as Shinji. The two of them, as Anno put it, "are unsuitable—lacking the positive attitude—for what people call heroes of an adventure. But in any case, they are the heroes of this story." She does, however, bear a passing resemblance to an active hero. She displays a poise and confidence in battle situations which Shinji does not. She seems to take real pride in winning battles, whereas Shinji just seems traumatized for most of them. Yet the first time we see her, it's a photo she's sent to Shinji along with Gendo's request for him to come to NERV Headquarters. Of course, Misato sends a flirty picture displaying her cleavage, but also draws arrows pointing to her breasts with the comment "pay attention". It's a little on the nose, but it works. She's not confident that a picture of herself, an attractive woman in her late 20s, will appeal to Shinji; but more importantly, she insists that he view her as a sex object. In the second episode, Misato decides that Shinji will live with her, rather than in some godforsaken bunker at NERV Headquarters. In the moment, we're just relieved that maybe an adult will show him some kind of kindness and affection. As the series proceeds and we're exposed to Misato's alcoholism and thinly veiled depression whilst their relationship becomes more fraught with tension and sexual ambiguity, maybe the best we can hope for this boy is that he is left alone and not taken advantage of.

Rei is in many ways far worse off than Shinji. She seems calm, collected and efficient. More simply, though, she has simply accepted a worldview in which she is an object to be manipulated by others. In her school uniform, she looks awkward and uncomfortable in her own skin. She's in her element, and almost graceful and beautiful, in fact, when she's in a plug suit-- a part of the machine. She rarely speaks because she has no expectation of being a person; it is only when Shinji does bring this expectation into their dynamic that she begins to think that maybe her life could be different. In one of the pair's first scenes together, Shinji somewhat creepily enters her apartment and finds what appear to be his father's cracked glasses on her dresser; this gave me a sense of foreboding I couldn't quite put my finger on. Rei is hardly bothered by the debacle that ensues except for the fact that Shinji has the glasses; she seems to have no sense of personal space and no sense of violation from Shinji (albeit accidentally) touching her inappropriately.

The scene shows Anno's and episode director Keiichi Sugiyama's attention to detail, and the show's capacity for the power of suggestion. The apartment is sparse; bare, in fact, except for a bed, a dresser, Gendo's glasses, and a bunch of tissues and bloody bandages on the floor. Why are the tissues there? Does Rei have a cold? I think not. The bandages are remnants of her injury, but they get the subconscious going about blood and the female body. Then you have to wonder about the tissues. Then about Gendo's glasses. Then about her weird attachment to him. And then you see just how unconcerned she is with being groped. In all of a minute, a major aspect of Rei's character is delivered without any dialogue pertaining to it. It's also the last indication of it until much later in the series, but it defines every time she talks about Gendo, leaping to his defense and showing uncharacteristic aggression.

Despite its monster-of-the-week quality, the show resists falling into a formula due to the episodes being structured around the characters' personal experiences, rather than the battles. Several episodes (most of the more important ones, in fact) are devoid of battles, as the conflict between the characters is more than enough, especially upon Asuka's introduction. The Angels, while they are alien and inscrutable, often represent the Eva pilots' issues in sophisticated ways. Although the cables the Evas are attached to are actually called umbilical cables-- a fairly blunt reference to the Evas' origin--angels like Ramiel represent intrinsic fears or issues in the characters, not simply the theme of the week. Ramiel bores down into Tokyo-3 and towards NERV Headquarters, towards Rei's secrets which reside down there (even though we don't know it yet). Internally, Rei fears where she comes from. She lives in the present because her past is too complex, too frightening, too ugly to think about. Yet here is Ramiel, boring down through the walls of NERV Headquarters which, like Rei's psychological walls, ultimately cannot keep everything out. In the first of many gripping episodes in the latter half of the series (Episode 16), Shinji is trapped inside Leliel, the mysterious dark orb. When he comes to his terrifying realization ("Blood! I smell blood!"), it's clear that he's experiencing a primal adolescent fear: fear of being infantalized, of losing all agency. Subconsciously, he's realizing that although he's inside Leliel, the alien womb, is his state in Eva 01 all that different? Or is his personal life? Now, even during his transition to manhood, he still lives, moves and breathes at the behest of others.

Depression is not an intense, prolonged state of sadness. It's something else entirely: a lack of feeling and of meaning. It's this incredible dichotomy that keeps me coming back to Evangelion. Without a doubt in my mind, I think it is a show about depression. Despite this, the show makes you feel so much and means so much. The show is visceral in its take on psychology; the intense violence which the show builds up to in the latter half of the series matches the fever pitch of emotions within the cast of characters, but the physical violence can't shake me to my core the way that the directors of Evangelion (most notably Masayuki and FLCL director Kazuya Tsurumaki) portray both adult and childhood trauma. The show can be awkward, tiring, and painful to watch. When it comes down to it, though, no other series has really come close to saying anything to me as much or as well as Evangelion. I haven't quite explained exactly what it says, and realistically speaking I probably can't explain it all. But there's always next time.

P.S. I tried to make this post less spoilery for people who are just curious about the show but maybe haven't seen it all yet. The next post will be spoiler-tastic.

.png)

.png)