|

| You thought you'd never have to see this again, didn't you? You were wrong. Now feel my pain. |

The Internal Logic

Throughout the series, Brotherhood basically does away with any and all rules of science. I’m not saying the original series was realistic, but you at least got the sense that Sho Aikawa actually cared about making it consistent, and making it seem more like a science and less like magic. Like it had some relation to chemistry and biology, and Edward and Alfonse seemed like really smart people who knew what they were doing. And even though at the end it kind of defied all that by having alchemy basically be a way of exchanging pretty much anything through this cosmic being they call Truth, that was only at the very end, and it made Ed question everything. I liked how in the original series there was actually an emphasis on transmutation circles, and alchemy seemed kind of like a science that had a set of rules.

In Brotherhood, we have none of that. Ed and Al kind of come off as idiots half the time, because they don’t know what they’re doing and can’t... shoot red lightning out of their crotches... I’ll get to that in a second. But really, in Brotherhood I really lost the sense that anyone cared about the internal logic of how alchemy worked, and instead wanted to see lots of big shiny things and explosions. This is evident in the first episode: so Isaac McDougal is an ice alchemist, but... ok, you see Mustang’s alchemy works because he changes the density of oxygen molecules. It’s a transmutation of sorts... that can happen. There’s a lot of oxygen in the air. But there’s not that much hydrogen in the air. How is he making ice out of air? It might make sense if it was dry ice, but then how is he altering the temperature THAT dramatically without there being any physical effects on the environment around him? And how is Ed not getting horrible frostbite from touching it? No wait, they specifically say that it’s water-based! Oh- maybe it’s alkahestry. So then we can just ignore the logic entirely.

|

| Feel it, damn you! |

This leads me to my next gripe: alkahestry. This entire so-called science and why it is in the show is completely baffling. Like, I understand that there were Chinese alchemists as well as western alchemists, but alkahestry has no clear rules. It seems simultaneously unlimited in its scope and useless in resolving any conflicts. This idea could work, in trying to integrate how all forms of alchemy work in this parallel universe, but first of all the parallel universe angle is never really explored. And second of all, like I said, I have no clue how alkahestry works or what the rules are. So I cease to care and conclude it’s kind of crappy magic.

And at the end: I get that there are transmutation circles in play (which I still don’t fully understand), but what exactly is being exchanged, or sacrificed, or chemically altered? Souls? But what does this so-called transmutation do?! It’s just a bunch of magic pentagrams, there’s nothing scientific about it. Also, Father... has a bunch of shields protecting him at the end... that isn't alchemy! What is that, like life force? Why would he use that? Like, there are a limited number of lives he can just throw away, right? Why not just create an invincible shield around him using alchemy? Like adamantium or something? Wait, he transmuted a tiny sun? From what? How?! Is there anything in this scene that isn’t just a giant ripoff of Final Fantasy 7? And I appreciate that Ed defeats him at the end, because apparently someone told Onogi that the protagonist is supposed to beat the bad guy at the end, and they also reminded him who the protagonist was; but seriously, why is Ed able to defeat him by punching him when bombs don’t work?! There is no explanation given at any time. Hell, I guess since Greed jumped into Father’s mouth and then exploded inside him or something, we can just throw logic out the window. Because I don’t fucking care anymore, and neither do they.

|

| I'd rather take the body-swapping old lady. Seriously. Fuck this guy. |

In a show that's almost entirely about alchemists and alchemy, I lose a sense of characterization of both. I thought alchemists had a scientific outlook on everything. They understand the materials that they’re working with, and transmute them based on that knowledge. At least, that’s what they told me alchemy was. But in Brotherhood, we have Father and Hohenheim shooting red lightning from nowhere. I think this guy Irie is just some idiot savant who likes to see multi-colored lightning. And besides this, I would be really willing and able to suspend my disbelief in order to see some kind of emotionally engaging resolution to a conflict, but it never happens in Brotherhood. The enormous preponderance of philosopher’s stones throughout the show throws any claim to science out the window, but it happens way too early. It really doesn’t work when Kimblee has two philosopher’s stones in episode 30. And hell, even Kimblee’s alchemy makes some sense. But what the hell is Father even doing half the time? This can work in a limited capacity, like when Alfonse is going to bring his dead brother back to life at the climax of the entire show. But character moments like this are when you can push the laws of the universe for the sake of the story. The villain swallowing God at the end is just dumb shlock, and it has absolutely nothing to do with alchemy or science.

The Production and Writing

Look, a big part of the problem here is that FMA is not Naruto. Naruto is a vast and expansive story spanning many, many seasons, detailing a huge world, not just the Konoha village, but reaching further into the sand village and beyond. There’s an enormous cast of characters; some of them memorable, some of them not. But even Naruto never lost sight of the heart of the show the way Brotherhood did. Even if Naruto Uzumaki wasn’t at the height of importance at that moment, you’d never have a whole episode without him. Plus, Naruto never held its focus so tightly on the main three characters as FMA did on the Elric brothers, anyway. FMA is a linear story, told in five seasons. It is not a 12-season epic spanning five years (in-world).

|

| This character is supposed to be 16. The pornography comparison was more literal than you thought, huh? |

Why am I comparing Brotherhood to Naruto, you ask? Because I think the producers wanted it to be Naruto. Naruto is the most successful manga and anime franchise in human history. The enormity and expansiveness of its media empire in Japan is incredible. I bet the FMA producers greenlit the awful scripts for the second half of the series thinking: “The huge cast of characters could be used to sell tons of toys!” Like I said, Brotherhood was a weird reboot thing coming right off the heels of the original series, but I heard really positive things about it. But rather than a dynamic re-imagining of the series that delivered a satisfying climax like I was promised, halfway through the series it turned into a weird combination of a cynical cash grab, a horribly convoluted and self-indulgent plot, and an awful cavalcade of painfully bad dialogue and editing. Brotherhood’s implosion was caused by a weird attempt to make the series something it’s not, and by the sheer incompetence of its staff, facts which are absolutely shocking considering that it is one of the most well-funded and highly-produced anime series in history.

The Philosophy

So why is Brotherhood so dumb? I think that Hiroshi Onogi and the series’ producers completely forgot what the series was about. This is solidified by the idiotic action movie that they dared to call Fullmetal Alchemist which they released a year later. Apparently Brotherhood was created to be a more faithful adaptation of the manga, but if that’s the case then I get the sense that Hiromu Arakawa’s writing kind of broke down, since the original series came out halfway through and ended before the manga did. I think she kind of let the spirit of the series get away from her because she was just trying to do something different from the show, rather than telling an effective story. It’s just appalling that the very person who created these characters- specifically Van Hohenheim, Scar, Mustang and the Homunculi- would ultimately make them less logical and effective than Sho Aikawa, who was just coming up with stuff and extrapolating because he was out of material to adapt. But while I haven’t read the manga, I have to imagine the ending isn’t as awful as the five episode screaming-and-explosion fest that closes Brotherhood, and turns FMA into a stupid action show.

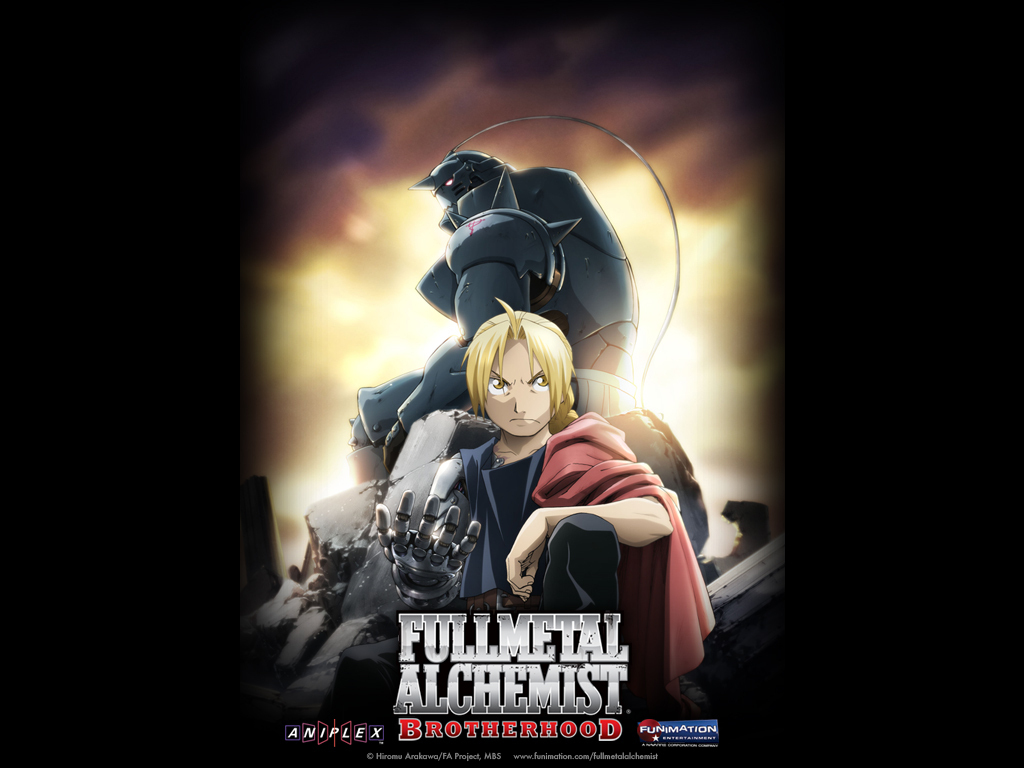

|

| What. |

This is especially offensive because the original FMA is one of the smartest animes ever written. It has very powerful portrayals and insights into ethical science, the existence of the soul, the existence of God or a life force over the universe, and it even kind of introduced a philosophy in itself: equivalent exchange, the irony of God, an arm and a leg. It was a dark show, filled with sacrifice, loss and death. But at the same time it was very tender. It showed a real relationship between two brothers. The love they shared, and the loss they bore. Two extraordinary boys pushed to the very brink of their abilities and will by the situations they got themselves into. But it was never for power or ambition, just for each other. Ed wanted Al to experience the physical world again: good food, the softness of his bed, a warm embrace. And Al wanted Ed to be able to feel like a normal person, to walk and swim normally again. Brotherhood barely manages to evoke this feeling at all, because it shifts the focus squarely away from the protagonists for huge parts of the show. At many points in the show I was left wondering what was going on, or why I should care. Hey, I thought this was a show about Ed and Al getting into adventures in the search of getting their bodies back!

But then at the end, Ed’s sacrifice to save Al was so profound and touching... that it was completely undermined by their friends taking philosophers’ stones and using philosophers’ stones. Ultimately, I don’t even know what these people are trying to say or if they even know what they’re doing. I even had a friend tell me this: “Ed and Al’s refusal to use the Philosopher’s Stone is just stubbornness. Their bull-headedness is what lost them their limbs in the first place. They apparently didn't learn the lesson.” Maybe he’s right; maybe it’s just me who doesn’t get Fullmetal Alchemist. But it makes me a little sad that Edward Elric and I are the only people in the universe who think that using a product of mass genocide is wrong in every circumstance. And maybe it’s just me who thinks that a show called “Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood” should be about the Fullmetal Alchemist. And brotherhood. And I guess the original series will be relegated to history as a poor first attempt to adapt a manga, rather than the brilliant, emotionally compelling, and well-written series it is.

|

| FMA and Brotherhood in one image: The well-developed, interesting, thematically challenging guy is swallowed by a big, dumb, lumbering, CGI-enhanced asshole. |

But I for one still contend that Brotherhood underwent such a profound self-destruction in its second half, that even the underwhelming villain and awkward climax of the original series is far superior in every way. So if you’re the kind of person who’s going to tell me that the original series sucked, and Brotherhood was way better, I can only assume that you just like shiny things and explosions, rather than logical, compelling, and emotional storytelling. To me that’s like saying that Revenge of the Sith is the best Star Wars movie. Look: just because it’s longer and bigger, and has more characters and CGI, and unending, tensionless fight scenes, that doesn’t make it good! It makes it exhausting! Look, Brotherhood is by no means the worst anime I’ve ever seen. It actually still has a lot of good moments, and some compelling characters. But when you take what is perhaps the greatest anime of all time, and you mess with the characters, and you add a lot of bad characters, and then you make it defy its own internal logic and philosophy... well, to me that’s even more offensive than just sucking in the first place.

.png)

.png)

.png)